A63 Castle Street

Our experienced team of archaeologists discovered a wealth of information about the lives of Hull society at a time when the population was rapidly expanding in the 18th and 19th century.

Trinity Burial Ground is located on the south side of Castle Street, and close to the busy Mytongate roundabout. It is associated with Holy Trinity Church, now better known as Hull Minster, which can be found in the Market Place, the heart of Hull Old Town.

We worked closely with Oxford Archaeology, Humber Field Archaeology, Hull City Council, Historic England, Humber Archaeology Partnership and Hull Minster to carry out this work along with our contractors for the A63 Castle Street improvement scheme, Balfour Beatty.

Here are just a couple of fascinating stories we discovered.

Female boxers at Castle Street burial ground?

Analysis of the injury types among the Castle Street population points to high levels of violence. One explanation for this may be the popularity of boxing during the 18th and 19th centuries, especially amongst the working classes.

Thirty-one skeletons from the cemetery have injuries such as fractures to the face (especially the nose), hand and multiple rib fractures which suggest they were taking part in boxing. Four of these 31 skeletons are female. Though boxing as a sport is usually associated with men, women’s boxing has been documented since the 1720s.

We will never know if the four females had sustained their injuries because they actively participated in the sport, or if they were fighting in other circumstances e.g., street brawling: where injuries were sustained to the women’s hands, these provide evidence that punches were thrown, and a bone was broken in the process. This information causes us to consider an aspect of the lives 18th/19th century Hull women, which might otherwise have been overlooked.

(Left: Nasal fractures, female skeleton. Right: Fractures to three ribs, female skeleton)

Under the saw: evidence for surgical amputation

At the time Castle Street burial ground was in use, surgery was still in its infancy and operations were high risk because antiseptic was not yet in use. Surgical amputation would only have been carried out if there were no other option and this was the only chance the person had to survive. A total of 13 amputations were found in the Castle Street assemblage, on 11 skeletons.

One particularly interesting case was a man who’d had his right leg amputated at midthigh level. This man is likely to have died on the operation table or shortly afterwards since the individual had been buried with his leg. The fact that his sawn-off leg was in the same coffin gives a rare opportunity to observe the cause for the amputation and surgical decision making.

The individual had suffered a fracture to the lower leg. The tibia and the fibula show signs of a significant deep bone infection (osteomyelitis). The infection was already in the bloodstream and his body weakened by the trauma and the subsequent infection, he was not resilient enough to survive the surgery.

(Surgical amputation: sawn femur from skeleton)

More about out work

Our work on site

Preliminary archaeological work took place in summer 2015 to assess the condition and location of burials, as well as providing a valuable insight about the lives of those buried. Initial analysis of the skeletons suggest that several conditions were prevalent at the time, including arthritis and the spine condition, spondylosis.

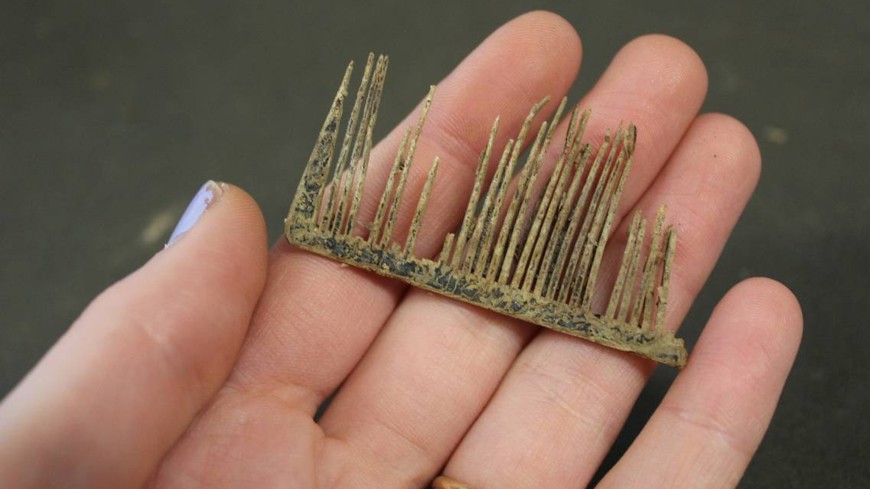

There was evidence of coffins including several with nameplates which were no longer readable and various types of handle, which can be dated from their styles.

There were also various buttons and pins from clothing, shrouds, and some hair.

The team of 70 archaeologists are working to the highest professional and ethical standards to carry out this substantial archaeological investigation, allowing the funerary remains to be carefully and respectfully excavated.

Two large tents have been erected to provide privacy and protection of the excavation areas which will take around a year to complete. After which we’ll restore the remaining area of the burial ground and rebury the remains.

The River Hull

The River Hull used to flow into the Humber Estuary along the route of what is now Commercial Road and Manor House Road.

This would’ve been a prime focus for settlement and economic activity recorded as Wyke upon Hull in the 12th century.

Some time during the 13th century, the Old River Hull appears to have become blocked and its importance was overtaken by the current course of the River Hull.

This led to changes in the settlements so that by the late 13th century, when Edward I took a keen interest in the town and it was named Kingston upon Hull, the main settlement focus was Hull’s Old Town.

Limestone and stone buildings

We’ve found the partial footprints of two buildings at the east side of the Commercial Road site which don’t show up on any post-medieval maps which suggests that they are of medieval or early post-medieval date.

One of the buildings, constructed in limestone, was associated with a single fragment of a vessel made in Beverley in the late 13th or early 14th century. The other was built on top of the deposit that contained 13th to 14th century pottery. It had limestone elements and the remains of a brick sleeper wall. Brick has been used in Hull since the early 14th century.

While the date and purpose remain unknown, the buildings could be significant for the history of Hull. They are well constructed and would have been expensive to build as stone would have had to be brought into the area.

It is thought the buildings could be connected to the poorly understood settlement of Wyke, documented in the 12th and early 13th century.

The timber yard

The Industrial Revolution and increased international trade during the 18th and 19th centuries transformed Hull into a large modern port, exporting manufactured goods from the industrial districts in the north of England and importing the raw materials that these industries needed.

Along with iron ore, one of the principal imports from Scandinavia was wood, and the significance of that material is apparent from the 1893 maps.

A sawmill can be seen in the north-eastern corner of the burial ground, on the site of a former gaol, and there are several large timber yards in the area.

The early 19th century maps shows a large warehouse built just outside of the burial ground to the west, which was serviced by a network of railways associated with the railway dock.

Rows of substantial upright pine timbers from the warehouse were found during the preliminary dig and the timbers have been clearly burnt, something that is thought to have occurred when the site was hit by an incendiary bomb during the Second World War.

Aerial photographs and maps show that the building was rebuilt on the same footprint.

Late 18th century jail

A late 18th century jail – or gaol as it was known then - stood at the north-east corner of the burial ground at a time of prison reform when the likes of John Howard and Elizabeth Fry promoted the need for better conditions, productive labour and religious instruction.

The Castle Street prison appears to fit a new model of prison design proposed by John Howard including six large rooms and 13 smaller individual rooms or cells.

It was known as the New Gaol, replacing the earlier House of Correction on Whitefriargate. It housed prisoners awaiting trial and those convicted of minor offences, as well as for prisoners awaiting transport to penal colonies like Australia. It closed in 1829 when a new gaol was built on Kingston Street.

By 1869 the plot was redeveloped into a sawmill by the later 19th century and by a brass and copper works (to the east) and a lead plant (to the west) by the early 20th century.

All that remained visible of the Castle Street New Gaol were the heavily leaning walls that formed the western and southern perimeter of the gaol yard, separating it from the burial ground. These walls were built of typical Georgian bricks and had survived to about two metres high. Excavation of this area should reveal the plan and internal organisation of the gaol, whilst historical research may tell us about the inmates themselves.

Image gallery

Some of our findings at A63 Castle Street.